These Indigenous comedians aren’t just funny, they’re using humour to tackle social problems, combat racism and start difficult conversations

Story by Laura Howells

Humour is an integral part of Indigenous culture. Saulteaux comedian Vance Banzo says it’s “same as  needing water, breathing…It’s embedded in who we are.” So it makes sense then that across Canada, Indigenous comedians are stealing shows with their quick wit and unique perspectives. But for some, comedy can spawn more than just laughter. Coming up, meet four Indigenous comedians who are using comedy to explore social problems, combat racism, and start conversations … but mostly they just want to make you laugh.

needing water, breathing…It’s embedded in who we are.” So it makes sense then that across Canada, Indigenous comedians are stealing shows with their quick wit and unique perspectives. But for some, comedy can spawn more than just laughter. Coming up, meet four Indigenous comedians who are using comedy to explore social problems, combat racism, and start conversations … but mostly they just want to make you laugh.

The past few times Vance Banzo has performed at open mics in Toronto, he’s found it hard to get through his sets.

It’s not because of heckling or stage fright – he just kept veering into conversations with the audience.

Banzo tells a joke about being Indigenous, someone in the crowd responds, and suddenly they’re having a discussion about Indigenous issues.

“It’s not like people are booing me or stuff like that. People are engaged,” said Banzo, a Saulteaux comic from Edmonton.

“They give a little knowledge, I give a little knowledge, then we start having a conversation…I think people want to understand.”

Banzo has always wanted his comedy to be meaningful. He grew up watching Charlie Hill and Don Burnstick, Indigenous comics who used jokes to subvert stereotypes and make political statements. He wanted to do the same.

On stage at a club downtown, he turns to his audience.

“Here’s something you didn’t know. Being treaty, I do get glasses once a year from the government,” Banzo says.

He pauses.

“So I guess we’re even now.”

The audience erupts in laughter.

Being Indigenous is a big part of Banzo’s set. People notice he’s a “big Native guy” right off the bat, he said, and they want to hear his distinctive voice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jZhd5-JZoTo

Banzo calls himself a “concrete native”–an Indigenous person who grew up in the city. His family is from the Fishing Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, but he was raised in Edmonton. A few years ago he moved to Toronto to study comedy at Humber College, and now he’s working the city’s comedy scene, performing stand up and sketch whenever he can.

“I want a voice. I want to say something. I don’t want to end up being a punchline,” he said.

“But at the same time I want to make people laugh. That connection’s too good not to have.”

While Banzo says he wants to use humour to “open up eyes,” he also sees comedy as a form of healing. At Humber, Banzo produced a one-man show about the impact residential school has had on his grandmother, mother, and now himself.

“That [show] was a big form of healing for myself. And it helped me open up,” he said.

“Because I’ve come a long way since I was a kid. I used to get bullied for being native all the time, and I was kind of ashamed. I once told somebody I was Filipino just so I wouldn’t have to tell him I was native.”

Read the transcript

Banzo says needing humour is “the same as needing water,” for Indigenous people. With so much sadness and pain in Indigenous history, he says laughing might be a way of healing for everyone.

“There aren’t very many news articles and news stories about how 25 Ojibway people just laughed and couldn’t stop laughing in a community hall.

“If you ever get the chance to just hang out, have dinner and just enjoy time with the Aboriginal community, I implore you to do it. It’s amazing,” he said.

“Thank the Creator he embedded that in us. That we can just always laugh and always find comfort in our community and in our family.”

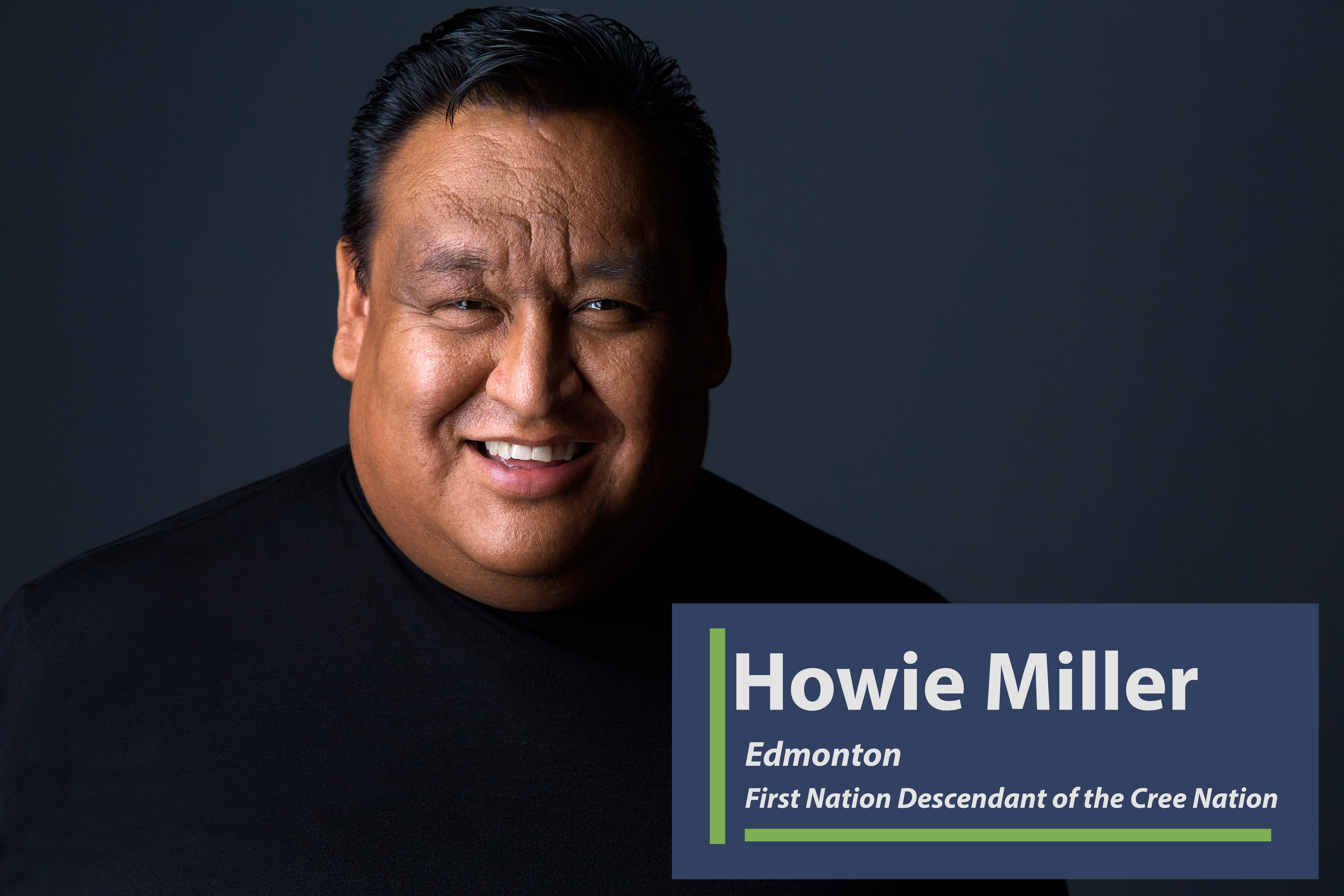

When Howie Miller first started doing stand up, he didn’t want to talk about being Indigenous.

He wanted to be a comedian who, “just happens to be native.”

As an adopted Cree kid in a white Edmonton family, Miller struggled with his identity.

He didn’t have any Indigenous role models growing up, and he’d sometimes hear older people make derogatory jokes.

Although his friends and family didn’t treat him differently, Miller said he still internalized a lot of negative attitudes towards Indigenous people.

“I took it upon myself to think that I was, you know, a greasy drunk Indian,” he said.

“I guess it’s the scared, vulnerability thing of not knowing where I come from…And the only people I saw of where I came from growing up were the Natives that were homeless downtown. So at a very early age I attached myself to that.”

Getting over those feelings took a long time.

But as he kept doing comedy, Miller realized people were interested in material about Indigenous life. There weren’t many Indigenous comics on the scene at the time, and he found that writing about his own experiences came easier for him.

Nowadays, being Indigenous is the first thing Miller talks about when he goes on stage–he calls it “addressing the elephant in the room.” He also strongly believes in comedy as form of education.

“What do you call a Native person that has his pilot’s license?” he’d ask his audience.

There’d usually be silence.

“A pilot, you racist.”

This joke makes people laugh, Miller said, but it also makes them think about their own ignorance.

“They expect some sort of racist joke because they’re not thinking that an educated ative person could become a pilot,” he said.

“I like letting them into the world that some urban Natives live in, and saying it’s not what you think.”

But Miller remembers a few times at the beginning of his career when audience members would call out racist jeers during his sets.

He’d handle the comments smoothly on stage, he said. But driving home, he’d cry the whole time.

Read the transcript“It really hurt. And I didn’t want anybody to see that,” he said.

But as his comedy career developed, Miller adjusted his act to make sure those jeers wouldn’t happen.

“You try to be their friend first, so they wouldn’t think to insult you,” he said.

“So that’s what really I’ve designed my act to do, because I don’t want to get hurt.”

These days, Miller is largely focused on corporate comedy gigs and working on his APTN sketch comedy show, Caution: May Contain Nuts.

He’s hopeful about that Canadians are starting to better understand Indigenous issues and talk about them more openly.

“Thankfully with social media, people who didn’t have a voice before are finding a voice,” he said.

“It warms my heart to know that people are being educated about it, and it’s getting out there.”

When Dawn Dumont started doing comedy in Toronto, she wanted to do jokes about what it’s like to be Indigenous and grow up on a small reserve.

But, she said, certain jokes would just make the audience, “feel sad.” Some people would laugh, but others would just seize up and dampen the whole mood.

“It’s really weird. You know that guy, ‘you might be a redneck if?’ When he does those jokes about poverty and dysfunction, people think they’re funny. But when an Indigenous person does them, they feel sad,” said Dumont, who said she’d get a lot of ‘awwws’ from the crowd.

“So I could never do jokes laughing at how backwards I was, or how my cousin lived in a trailer and someone had stolen the wheels off it. I couldn’t joke about those things.

[…]

“I think because they feel sorry for Native people.”

That didn’t stop Dumont, however, who always kept “motoring along” onstage.

Dumont is a Cree comedian who grew up on the Okanese First Nation in Saskatchewan. She’s worked the comedy scene in Toronto, New York and Edmonton, but is also a playwright, author and columnist–and she holds a law degree. She’s publishing her third book in May, and she co-hosted the APTN show, Fish Out of Water with Don Kelly.

While doing stand up, Dumont said she sometimes struggled with how audiences responded to her subject matter, which would often poke fun at racist stereotypes.

“You feel like, if I’m laughing at racism then am I making it ok to be racist?” she said.

Dumont had one bit, for example, where she’d joke that she was OK with people calling her “squaw,” because she had an aunt called Auntie Squaw.

One night after telling that joke, she remembers walking out of the comedy club and a guy yelling, “have a good night, squaw!”

“Obviously he meant it in a joking way…but then my friend said, I don’t think the average guy gets the whole ‘n word’ thing,” she said.

“It is a weird line. The thing is, I’m writing a joke sometimes to make people laugh. Then maybe other times I’m writing a joke to make a point. And it was hard to get that across.”

Ultimately, Dumont says, she had to stop thinking about what people would do with her jokes once she walked off stage.

“I would just sort of remind myself that even being on stage was like, of an act of rebellion against what people expected,” she said.

“Just being an Indigenous female in front of them, talking to them.”

At the same time, Dumont said she sometimes resented that she couldn’t just “be a regular comedian.”

“I always felt like I wasn’t good enough that I couldn’t just be a regular comedian talking about regular stuff,” she said.

“Whatever that is.”

Now living in Saskatoon, Dumont isn’t doing as much stand up as she used to. She has a young son, works a full-time day job, and is publishing her third book in May.

Dumont says writing feels like a better place for her now, because she can provide a lot more context than she can onstage.

She remembers, for example, feeling conflicted when she would tell jokes about her dad being an alcoholic.

“He just did all these amazing things and he just such a talented, intelligent person. And I always felt kind of bad that I was talking about him being an alcoholic…I would feel like that’s the only thing people took away from those jokes,” she said.

“You can’t really talk about real things on stage.”

“So I’m First Nations, I’m an Ojibway person. Any of my people in the house?”

Usually there’s silence.

“Wow, when white people wipe out a race they’re thorough, huh?”

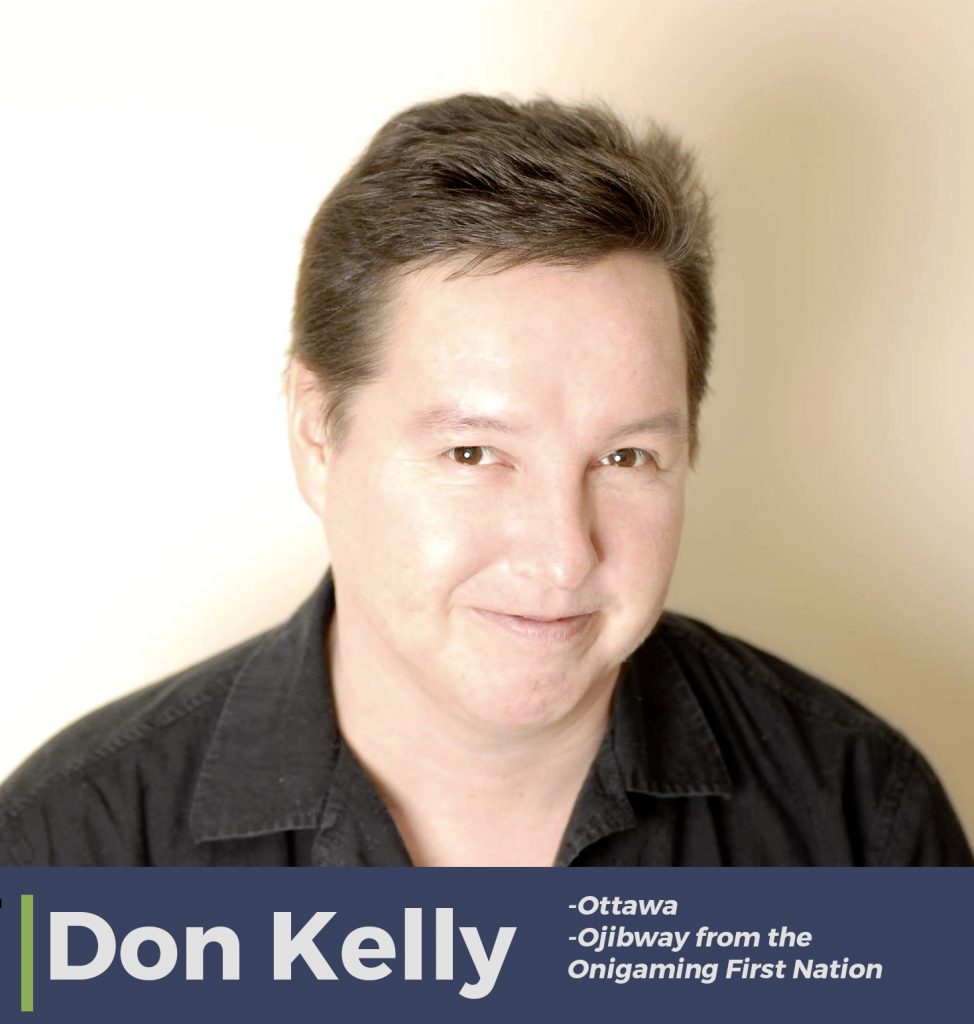

Don Kelly loves telling this joke. People laugh, he says, but there’s often some “oooohs.”

He doesn’t mind.

“I’ll say, ‘too soon? Sorry to drop the history bomb on you,'” Kelly said.

“If it makes people think about it or confront it, that’s okay with me.”

Kelly doesn’t set out to make a point in his comedy. He just writes jokes he thinks are funny.

But if he can make change some minds along the way, that’s a bonus.

Here’s one joke he’d tell earlier in his career:

“People ask me if, as a First Nations person, do I celebrate Thanksgiving?

“I say, yeah, last year I had a traditional Native thanksgiving. The European guy who lives next door came over, claimed he’s discovered my apartment, now he’s living in the place.”

Kelly said that if people get the joke, they get the point.

Kelly does have one rule, however: never “play up” negative Indigenous stereotypes. That’s just easy and cheap, he said, and gives people who actually believe the stereotypes permission to repeat them.

Kelly loves doing stand-up, but it isn’t his full-time gig. The Ottawa-based comic is also the communications director for the Assembly of First Nations, and he used to co-host the APTN show Fish Out of Water with Dawn Dumont.

Although he’s a member of the Ojibways of Onigaming, a Treaty #3 First Nation in northwestern Ontario, Kelly says people are often surprised to learn he’s Indigenous. His mother is Swedish, so he used to jokes about how he didn’t “look Native.”

But Kelly always wanted to make his Indigenous identity part of his comedy. For one, he liked audiences to see Indigenous people in an unexpected environment.

“People who didn’t know Indigenous people thought we were always stoic, or always lamenting the loss of language and land and the history,” he said.

“When in fact there’s so much laughter in First Nations country […] Humour has always been there, at least for my people.”

Kelly recounts community elders telling trickster stories steeped in humour, and powwow announcers sending rooms into fits of laughter.

‘People might think oh it’s a reaction to tough times, it’s a coping mechanism, but humour’s always been there,” he said,

“People who know Indigenous people will say to me, you guys are funny. And if that’s a stereotype, I’ll take that one.”

Email Laura Howells at lhowells@ryerson.ca