Understanding the issues around Indigenous homelessness involves looking at the concept of ‘home’ as more than just a place to live

Story by Melissa Galevski

Feature image courtesy of Ken Armstrong

It was 1996 when Jesse Thistle moved out west to live with his brother in Vancouver and was kicked out shortly after for using drugs, an affliction that began at the tender age of 15.

He was homeless for the first time.

Thistle started living in a car with a friend and began experiencing episodic homelessness thereon after.

“Every couple of months I would be homeless. I’d get my welfare cheque, get a place to stay for a month or two, spend my welfare, wouldn’t be able to make rent, then I’d get kicked out,” Thistle said.

He spent time on friends’ couches, frequented shelters and even lived in apartment staircases, a pattern that continued until he found himself living on the streets, and then in and out of jail.

In 2005, he robbed a corner store, an event that oddly marked the beginning of Thistle’s path to healing. He eventually sought treatment, got sober and reconnected with his grandmother, whom he promised to get his education, and eventually made it to York University.

Thistle is Métis. He started tracing his Indigenous roots in his undergrad, at which time he began to formulate his identity as an Indigenous person. He questioned why so many Indigenous people like him represented a disproportionately large segment of the Canadian homeless population.

In his current position with the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, Thistle began receiving his answers. As Indigenous Partnership Lead, he works with different organizations to address Indigenous homelessness and has been working toward defining the issue, a breakthrough that came when he began examining the concept of home.

Home, he found, was more than just a place to live.

What is Indigenous Homelessness?

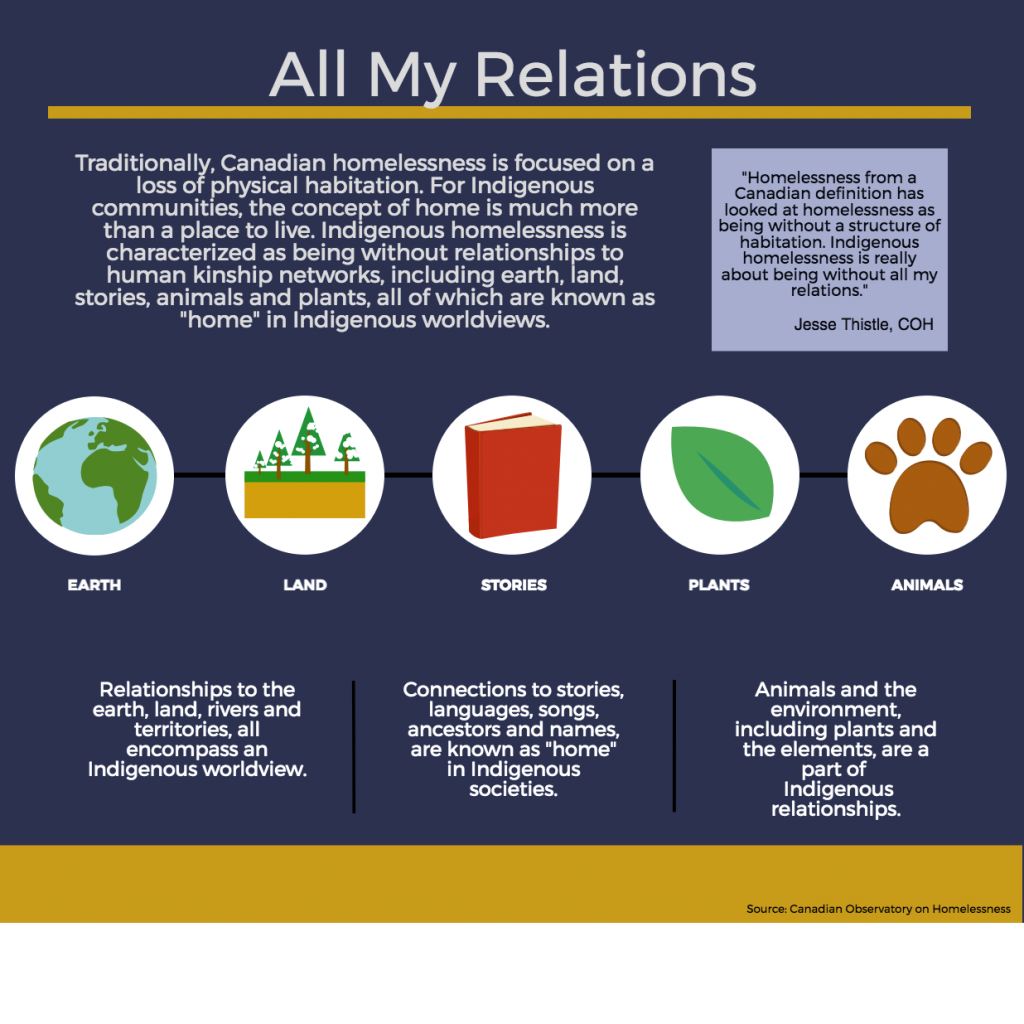

A Western perspective on homelessness has traditionally been defined as a lack of physical accommodation. In 2012, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness launched a formal definition of homelessness categorized by four typologies: unsheltered, emergency sheltered, provisionally accommodated and at risk of homelessness.

But Indigenous homelessness could not be measured as easily.

Having worked with the organization since 2012, Thistle was hired in 2016 to help formulate a working definition of Indigenous homelessness and began consulting with Indigenous communities.

“Indigenous homelessness is about being without relationships,” Thistle said. “It’s about being without identity, self, family, kin groups, land, ancestors, stories, rights of passage, languages, cultural institutions – all these things were systematically cut away and it cut us away from our worldview of all our relations,” he said.

Thistle uses the Anishinaabe understanding, all my relations, to describe these aspects, all of which are known as “home” in Indigenous societies.

Being without all my relations is not about what Indigenous people are lacking, but rather, it is a direct reflection of the systemic and structural deficiencies created within Indigenous communities by the state, the expression of which is seen on the streets.

“A lot of Canadians have equated that Indigenous homeless people are homeless because of their Indigeneity, when it’s the opposite that’s true. Indigenous people are homeless because they have been disconnected from their Indigeneity,” Thistle said.

The Compounding Effect of Intergenerational Trauma

Thistle spent many years divorced from his culture.

He was born in Prince Albert, Sask. and raised by his paternal grandparents in Brampton, Ont. His mother left when he was a child and his father lost custody of him and his two brothers after robbing a store – just like Jesse would do decades later – before disappearing in 1982.

“I grew up not knowing where my dad was and that I was unwanted by my mom and so I was resentful that I was Indigenous, but I really didn’t understand what that meant either,” Thistle said.

Thistle can trace his family back to the Morrissette-Arcand clan, a Métis family from Saskatchewan that suffered intergenerational trauma since being displaced from Red River, Man. in 1869, and came to live on narrow swaths of public land called road allowances in the twentieth century.

Much of Thistle’s academic work has focused on historicizing the intergenerational trauma of his ancestors. For Indigenous peoples, this trauma extends from historical and institutional failures, including colonialism, land grabs and residential schools, which served to separate Indigenous populations from their Indigeneity.

And here laid the root of Thistle’s resentments, addictions and homelessness – all expressions of trauma compounded over generations.

“It just kind of illuminated everything,” he said. “I look back at my parents’ lives and I could see that they were impacted by it [intergenerational trauma] and that’s why they let us go. I could see that my grandparents were impacted by it and that’s why they didn’t really help my parents,” Thistle said.

The impacts of Indigenous homelessness are magnified for a younger generation, particularly those living in urban centres or foster care, and that have been completely separated from their kin, land and identities as Indigenous peoples. This absolute dispossession that often results in homelessness, Thistle says, is the only logical outcome.

Walking Wind was admitted to children’s aid after enduring abuse at the hands of his father. He entered a revolving door of foster homes before reuniting with his estranged mother, that is, until their rocky relationship took a turn and he moved out of her home.

He was homeless and began living in shelters.

Walking Wind is Métis-Cree from Calgary, raised in Toronto. He began connecting to his Indigenous heritage in his mid-teens, which became difficult when he started living in shelters. Many non-Indigenous shelters would not accommodate his cultural teachings, and were indifferent to him performing ceremony and smudging.

“I still tried to follow teachings as best as I could. Sometimes in that environment it’s not that easy,” he said.

Walking Wind visits the Native Child and Family Services of Toronto’s youth drop-in centre almost every day. At 26, he is no longer considered a youth, but has been allowed to come over the age limit. He credits the centre as a safe space, which has led him to forge meaningful relationships with fellow youth and staff.

“Home is being felt welcomed in your own community. As Indigenous people, we see family as not just blood family. We see family as the community,” Walking Wind said.

The centre has also allowed him to reconnect freely to his Indigeneity through cultural and spiritual practices, both in and out of the centre.

He attends a weekly drumming social at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto, an experience that Thistle credits as a great source of healing and strengthening, and an event that could help mitigate the epidemic of Indigenous homelessness for future generations.

Thistle also credits the power of the urban landscape in providing ample opportunities for Indigenous peoples to rediscover their history through various social gatherings and education systems.

“Cities are also an urban Indigenous space and if we come to recognize that, then we can reconnect people right here [in Toronto],” Thistle said.

But the city doesn’t shine bright for everyone. The history of Canada is so dominant, Thistle says, that it has completely replaced an Indigenous narrative – erasing Indigenous contributions, struggles and their rightful places as first peoples of this nation. Many Indigenous peoples cannot imagine the city, or Canada for that matter, as a truly welcoming space.

Thistle is currently working towards a PhD in History at York University and continues to examine the concept of home in his research with the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

For Thistle, home is now a restoration of relations. In 2013, he returned to Saskatchewan and reunited with his mother, an experience that anchored him to his family, to the land and back to his Indigeneity.

“I have good social webs of significance that I’m embedded in now, that’s my home.”

Email Melissa Galevski at mgalevski@ryerson.ca