Canada is celebrating 150 years since Confederation on unceded Indigenous land. Critics share their perspectives on what these controversial celebrations reveal about the possibilities of reconciliation in Toronto

Story by Iris Robin

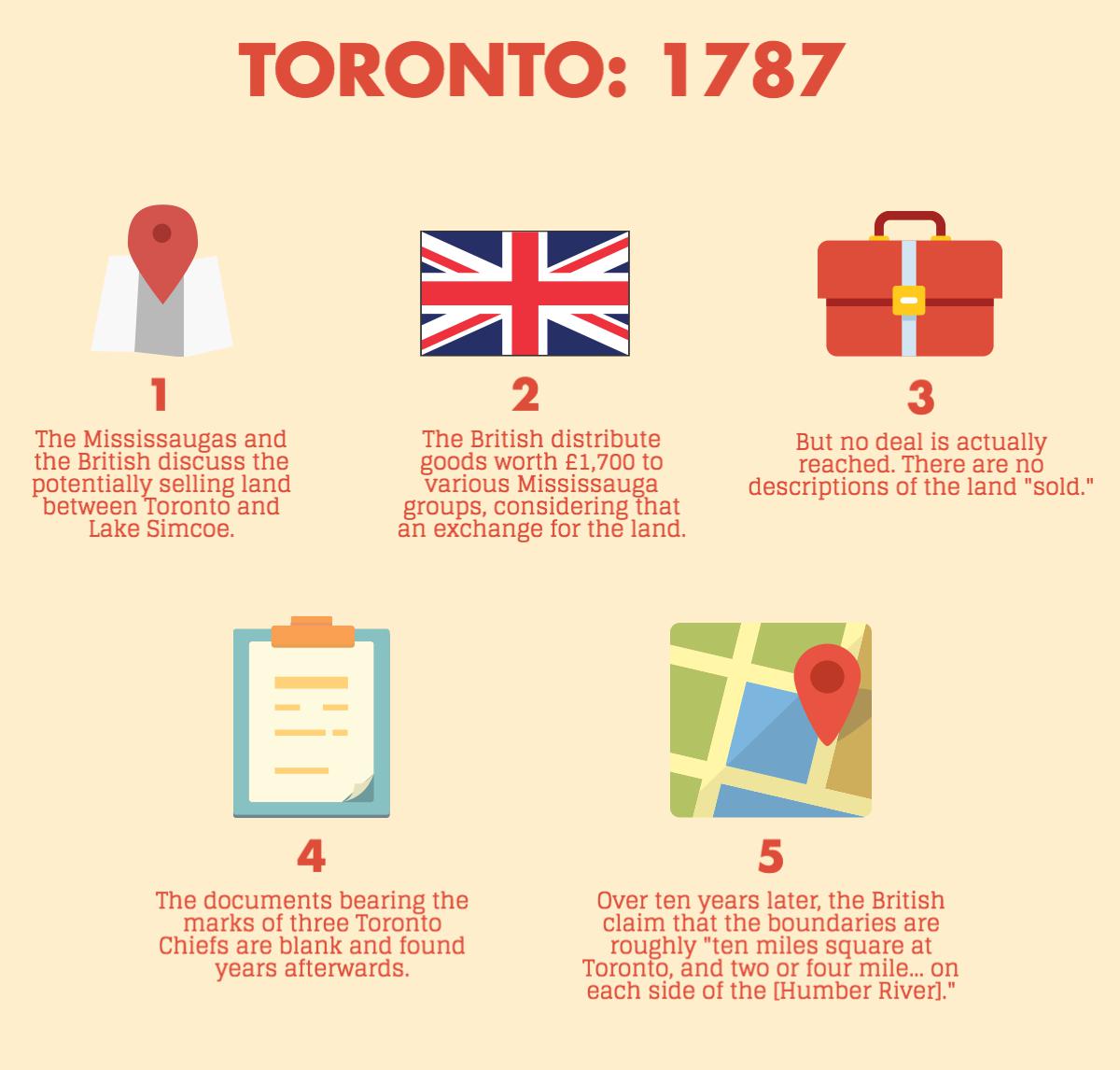

At a time when Canada is celebrating 150 years since Confederation, the tensions between this landmark anniversary and Canada’s ongoing colonialism are entrenched in the very land on which  we live.

we live.

Deborah McGregor is from the Whitefish River First Nation, Birch Island, Ont., lives in Toronto and has done for more than 30 years.

“Toronto was a bit of a shock,” she said. “I remember noticing so many fences, like people fencing off their properties. People didn’t do that where I came from. You could just cut through somebody’s yard on your way to go berry picking or something, or to go fishing down the bay or whatever,” she added.

As an associate professor at York University’s Osgoode Law School and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Environmental Justice, McGregor has noticed that people are becoming more territorial. But it wasn’t always like this when she was younger. “You knew everybody, everybody was a First Nations person. But you had to go to school off-reserve and that was not fun, but where I was, like in the community itself, Toronto is dramatically different.”

Despite the differences, McGregor says that Indigenous peoples who live in urban settings still retain the knowledge and cultural practices that are important to them. “It’s not like you go from the north and come into the city and magically leave your brain as soon as you enter the urban setting. It just looks a bit different,” she said.

“There aren’t people hunting and trapping in downtown Toronto. But people still have that knowledge and they still find expression for it in different ways because a lot of it is how you relate to yourself, how you relate to your family, your clan, your communities,” she added.

City and culture

Cities can be hubs of cultural expression. Tucked away in a third-floor room at the University of Toronto’s Athletic Centre, Jennifer Sylvester and her team prepared for the first pow wow at U of T in at least 20 years in March, 2017.

Sylvester is from the Ojibwe/Southern Georgian Bay First Nation and is the president of the Indigenous Studies Students’ Union at U of T. She said that this is “an opportune time” to host a powwow, since it coincides with the release of the university’s Truth and Reconciliation Steering Committee report and with Canada’s 150. Sylvester saw it as a chance to introduce Indigenous culture to the U of T community and the broader Toronto community.

“We specifically wanted it to be a powwow to say “We want you to come. Come see how beautiful our Indigenous culture is. Come see, come hear our songs. Come see our dancing because we have different various types of dancing, and just come and see what a powwow can do for a community,”” Sylvester said.

The powwow took place on U of T’s downtown campus and included Métis Jiggers, Smoke Dancers, Aztec Dancers, and Inuit Drummers and Singers. Indigenous caterers and crafters were also there to sell their goods.

Indigenous songs are made up of sounds so that everyone can join in, regardless of spoken language. Listen to a national anthem performed by Inuit singers below.

Hundreds of people attended and Sylvester said that the event generated momentum and “created a new heartbeat on campus.”

“That’s just amazing,” she said.

In addition to bringing people together, Sylvester said that the event helped start conversations about reconciliation. “If the reconciliation actually means exploring what Indigeneity means, exploring what Indigenous culture means through a pow wow, people are willing to explore. That can be the starting point for many people to understand what reconciliation means and that means sort of understanding what the culture means and embracing it,” Sylvester said.

McGregor noted that a lot of Indigenous peoples actually experience Indigenous cultures for the first time while in an urban setting, especially because of the educational and programming opportunities there.

Sarah (not her real name), an activist from the Samson Cree Nation, first felt part of an Indigenous community when she moved to Toronto. She hadn’t had the opportunity before because her mother raised her and her sister away from the violence on their reserve.

Since she moved to start university, Sarah had access to classes in Indigenous studies, youth and cultural programs at the Native centre, and opportunities to attend events featuring Indigenous speakers.

“All those things were new to me after living in a mostly non-Indigenous rural area. Those things really blew my mind, and ignited a passion and purpose in me for the first time in my life,” Sarah says.

Urban colonialism

At the same time, Sarah began to grasp the extent of the damage done to Indigenous peoples, which gave her “new feelings of rage and hopelessness.”

Sarah fell back into her old habit of drinking, which had started because of a “gnawing emptiness.”

“I started to feel a hopelessness when I looked at all the cars in the streets and a rage at the buildings and at the concrete that shouldn’t have been built there,” Sarah said. After an overdose scare, Sarah decided to channel her despair into activism.

“So that is the story I think about when I think about Toronto and 150 years of Canadian colonialism,” Sarah said. She added that many of her relatives were in residential school or the foster care system. Her family’s roots are Plains Cree from Alberta, where the oil industry displaced them.

“I don’t feel it’s appropriate to celebrate,” Sarah said.

The next 150

McGregor said that knowing the treaties is a big part of the difference between the way in which Indigenous people and occupiers treat the land. The treaties, McGregor says, are a way of establishing responsibility and at the heart of an agreement like that are the questions about what it means to be a responsible person. In an urban setting like Toronto, it’s easy not to think about how the natural resources sustain life.

“I think it’s really easy to be disconnected,” McGregor said. On the other hand, Toronto’s proximity to the lake and its abundant green space should make it easier for everyone to connect with the land.

“It has to go further than that, it’s a sense of responsibility, the kind of place you want to live in 10 years from now, 20 years from now, the kind of place you want your descendants to live in, you have that sense of responsibility.

For McGregor, the significance of Canada 150 is that it has the potential to be a catalyst for change, reminding the country that its policies in relation to Indigenous peoples failed.

“We’re still here,” McGregor said. “Because the policy of the prime minister at the time and various ministers of Indian and Northern Affairs or Indian affairs was basically to eradicate the Indians. But we’re here we’re the fastest growing population, we still have treaties, we still have land bases, the connections are still there.”

Email Iris Robin at irobin@ryerson.ca